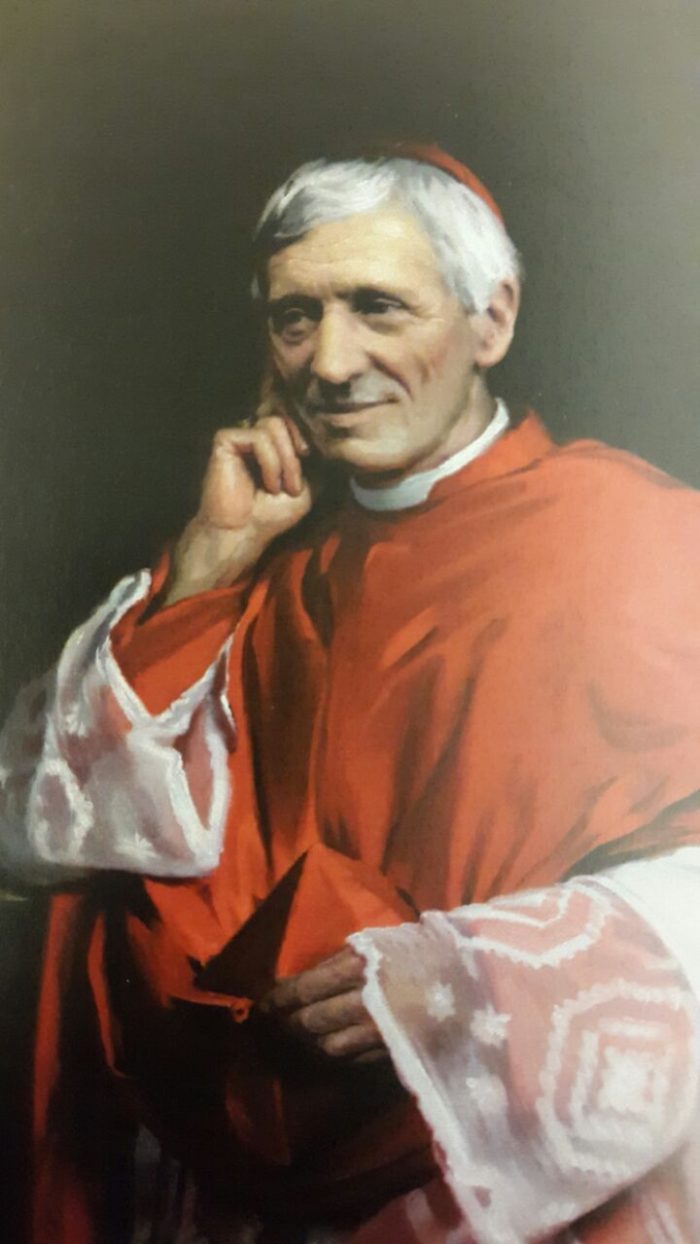

I would like to talk about a topic which is closely related to the theme of this year: John Henry Newman: Teacher and Minister in a University Setting. The fundamental thesis of my presentation refers to the continuity of Newman’s thought over the years; from his time at Oriel College as a Tutor (1826) to his time at Birmingham in the 1870’s.

Even though he became a Roman Catholic in 1845, the key pieces of his teaching display a coherent development over the years.

This development can be seen in Newman’s University Sermons VII and VIII as well as in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk. These three texts possess a magisterial value, both academic and pastoral — especially his reflections about temporal matters and matters of the faith.

For Newman, temporal matters include education, political organization, civil law and civil authorities. On the other hand, matters of the faith include dogmas, the correct interpretation of Holy Scripture, moral matters, and the legitimate authority of the Church in religious matters.

These two spheres are present together in the human beings, specifically in our personal conscience. The harmony between temporal matters and faith-matters ought to be independent in its authority and organization. However, in the life of citizens, and believers, these two spheres ought to be perfectly harmonized. We are responsible for the use of our freedom in both spheres as well as in the cases in which our decisions affect both spheres.

Antecedents

Before discussing the content of the three writings that I have selected, I will briefly

Summarize the context in which Newman wrote these three works.

- Context of University Sermons VII and VIII

Even as a young Anglican clergyman, Newman knew how to combine his roles as pastor and educator — roles which he exercised at Oriel College as well as at St. Mary’s. Newman had the opportunity to give these University Sermons between 1826 and 1832, when he was named Select Preacher for Oxford University.

During this time, University sermons were surrounded by formalities and delivered by preachers designated ad hoc by academic authorities. Whether such designation was based on a recognition of Newman’s abilities or obtained by the influence of his friends has been variously interpreted.

In any case, Newman’s life can be summarized as that of a great pastor and a great academic. This dual effort is perhaps best seen in his role as preacher, where he combined spiritual theology and pastoral concern. So highly regarded was his pulpit eloquence that important people attended often attended his sermons.

His sermons had a recurrent theme: the relationship between reason and faith. The sermons effectively functioned as a platform for presenting his theological-philosophical reflections. Sermons VII and VIII focused on the abuses of worldliness and irresponsibility. These Sermons seem to respond to Newman’s discovery or a special insight into the mystery of human iniquity.

The social-political context of Newman’s sermons is an added factor. In 1828, Irish Catholics requested to be admitted to Parliament. Parliament approved The Emancipation Act because of Daniel O’Connell, a very charismatic lawyer and expert in English law; O’Connell sought civil freedom for the Irish so that they could also have religious freedom.

The presence of Roman Catholics in Parliament was an apparent contradiction. While Newman felt that every citizen should be represented in Parliament, he did not deem it appropriate that Catholics be members of Parliament because it was also responsible for certain decisions affecting the Church of England.

Furthermore, Newman felt that Catholics were not obliged by conscience to support the decisions made by Parliament that favored the interests of the Anglican Church.

This contradiction between the right of parliamentary representation and the anomaly of members of one church making decisions affecting another church led Newman to his conviction that Church-State separation was essential; in other words, the Church had to be independent from the Government.

- Context of the writing of the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk — 43 Years Later

The Letter to the Duke of Norfolk was written in 1875 in light of a concrete problem: relations between civil authority and religious authority. In 1869, the First Vatican Council was convened by Pope Pius IX.

One of the issues discussed at the Council was the definition of the «infallible magisterium of the Roman Pontiff.» The eventual definition stipulated the conditions under which the Pope could define a doctrine concerning «faith and morals» ex cathedra.

After reading the definition, which was promulgated on 18 July 1870, Newman personally did not consider this definition to be problematic for the Catholics; he felt that the new definition re-stated what the Church had basically taught for centuries.

However, the definition radically affected relations with other churches. Newman soon realized that the definition was being misinterpreted both by Catholics and non-Catholics. For example, some people interpreted the definition to mean that the Pope could never sin. However, infallibility is not the same as impeccability. The declaration on infallibility did not refer to the personal life — and sinlessness — of the Pope but to papal teaching about the interpretation of revelation in view of his responsibility to safeguard the doctrine given by God to the Church.

Even though many Catholic citizens of the United Kingdom felt that a definition might jeopardize their position within the country, a group known as the Ultramontane, which

Included the Archbishop of Westminster, strenuously supported the definition of the dogma. Subsequently, however, Newman’s foresight about the potential ill effects of the dogma was confirmed.

One of the most serious reactions against infallibility came from William Ewart Gladstone, who in 1874 published an article in the Contemporary Review which stated: “No one can be her (Rome’s) convert without renouncing his moral and mental freedom and placing his civil loyalty and duty at the mercy of another”. In effect, Gladstone’s statement charged that the doctrines of the Roman Church prevented Catholics from thinking and deciding freely in temporal matters. This was a direct attack on the civil loyalty of Catholics.

In replying to the former Prime minister, Newman not only had to defend himself but also had to defend the freedom of conscience of the Catholics of his country as well as their freedom to exercise their civic responsibilities. In January 1875, Newman published A Letter Addressed to His Grace the Duke of Norfolk on Occasion of Mr. Gladstone’s Recent Expostulation. The Duke of Norfolk, a well-known Catholic layman, was the ranking peer of the realm outside the royal family. Newman’s response, intended to refute Gladstone’s accusations, presented a treatment of the nature of conscience.

Newman’s Letter emphasized that the Catholic interpretation of church authority in general and infallibility in particular was not identical with that of the small group of Ultramontanes. In particular, Newman insisted that each person is responsible for his/her own words because everyone isl free and so responsible.

Gladstone gratefully replied: “Thank you for the genial and gentle manner in which you have treated me” and commented, “Your spirit has been able to invest even these painful subjects with something of a golden glow”. Newman’s discussion of conscience is still valid today, even though the original context of 1875 is long past.

Newman’s Doctrine about the Relation between Temporal Matters and Matters of Faith

After mentioning the circumstances under which Newman wrote Sermons VII and VIII in 1832 and his Letter to Duke of Norfolk in 1875, it seems helpful to indicate their central theme:

Sermon VII presents the characteristics of a worldly mentality; Sermon VIII describes the operation of conscience; The Letter to the Duke of Norfolk explains the compatibility of acting according to conscience both as a member of civil society and as a member of a religious society.

These three aspects can be connected in a philosophy that had been developed through the years under Newman’s influence. In general, from 1832, when he wrote his University Sermons. Newman considered it necessary for the church and the state to be independent from each another.

At that time, he referred to the Anglican Church as having its own authority, just as the British crown and Parliament had their supreme authority. Although Newman as an Anglican, opposed the participation of Irish Catholics in Parliament, he recognized the difficulties that derived from the interference of the Crown in religious matters. The arguments he presented in his Letter are basically the same ones that he utilized during the Oxford Movement.

The two fundamental assertions of Newman’s thoughts are:

First, in regard to church and state, they must be regarded as two independent institutions with their own objectives and means; each has a right to freedom so that it can fulfill its mission with the means it deems necessary.

Second, in the internal conscience of a person loyal both to God and to his/her country, a divided allegiance should not exist; rather there should be complete harmony. One cannot be a believer of the church and forget about patriotism nor can one be a good citizen and leave religious convictions aside.

Thus the principal topics in these texts are freedom and responsibility.

- Independence of Both Church and State in External Matters

The issue that Newman discussed as an Anglican preacher at St. Mary’s was treated again 43 years later when he defended the Roman Catholic position in civil matters. Some of the principal points of his exposition clarify what the independence of the church and the state is all about. This independence in external matters allows the freedom of church members in civil matters. Newman’s Letter explains the issues that are important to understand the situation of Catholics in a civil society.

Newman presumably remembered the events of 1829 and similar events in 1873 when the Irish bishops took steps to oust some Ministers of Parliament. Newman wanted to explain that the bishops had a right to intervene in civil matters insofar as they were exercising their rights as citizens[1]. The bishops did not act in their role as religious authorities; rather they legitimately participated as citizens in the affairs of their country.

In regard to the external and real authority of the Pope, Newman explained that his mandate refers to the definitions of supernatural truth, which ought to be believed. The pope also legitimately interprets natural moral law because the author of this law is God and if the pope is understood as being enlightened by God in interpreting the Holy Scriptures, this teaching becomes easier to understand.

One interesting clarification is that the decisions of the Pope in matters of faith are only about essential doctrinal issues on a theoretical level, not judgments about specific concrete cases. Similarly, in moral matters, the legitimate interpretation of the Church referring to natural law is only theoretical. Newman[2] emphasized that the definition of «the infallible magisterium» of the Pope extends solely to the doctrinal area and not to concrete solutions to problems. This is the reason why it has been said that “the infallibility may affect a theologian, a philosopher or a man of science, but a politician has a distant relation with it’[3]. In practical matters, ecclesial authority and its guidelines do not decrease the freedom of people. On the contrary, people have the liberty to choose responsibly the way they will apply general norms to their concrete circumstances.

- Responsibility as the Harmonizing Element between Temporal Matters and Matters of Faith

Newman’s primary interest was to demonstrate that there is no reason for a citizen to have divided loyalties: civic and religious. The nucleus of this issue is found in responsibility. This is the point that harmonizes the diverse spheres of a person as citizen and believer.

Sermon VIII, preached on Sunday December 4, 1832, was entitled “Human responsibility, as independent of circumstances”.

Newman takes from Aristotle the notion of actions: all actions are voluntary if we are their ultimate end or their active beginning in one way or another. Consequently, we will receive blame or praise for the results of our actions because of our behavior and not for the circumstances in which these actions occurred[4].

In Sermon VIII, Newman pointed out the relation between the responsibility acquired from an act and the circumstances, which are not an excuse to exempt a person from responsibility. In some cases, circumstances can increase or decrease guilt or increase or decrease the motives for praise Each person is the cause of his own improvement or misfortune and not external assistance or obstacles. Newman pointed out that not even divine grace can annul freedom. Each person should carry his/her own load… «Don’t deceive yourself: what you sow is what you reap»[5].

The responsibility that Newman referred to in this Sermon is concretized by two factors: first, our freedom does not exclude the dependence on our divine origin since we exist because of God, who is the one who keeps us in existence. Second, the influence of the circumstances on our acts has a secondary importance.

Excuses are ways of deceiving our conscience with sophistic reasoning in different situations in life. Excuses originate when we consider freedom as a synonym for independence and the lack of independence is viewed as slavery.

Newman mentioned some of the most common excuses. One excuse is when we imagine that the concrete situation is especially difficult and in order for one to be better and happier, the situation must change. A second excuse is based on the sophism of apologizing on a specific occasion because we felt that we were victims of a particular coincidence of circumstances. Yet another excuse refers to the lack of education to justify a disorderly way of life. The list of excuses and sophisms goes on and on but they all distort reality to one’s own self-satisfaction and to justify the lack of responsibility.

To Newman, our imagination can easily assume duties abstractly. The difficult part is understanding and committing oneself to the real and concrete duty. When responsibility is acquired in a precise and effective way, when it comes to us surrounded by problems that must be solved, then this responsibility becomes arduous and distressing.

If we apply the doctrine discussed in Sermon VIII to a concrete situation, the issue is very delicate. It is even more delicate when the rights of minority citizens are at stake, especially when society wants to take away their human rights such as freedom of religion and of speech and the right to be represented in civil proceedings.

If their freedom is limited in external affairs, it is also possible to attack them with the sophism that their obedience to the Pope is loss of their freedom. However, it is not the obedience but the manipulation and deceit, which unconsciously influence their conduct and limit their freedom. Obedience is identifying one’s will with the will of those who govern. In this case, obedience presupposes liberty and people do not lose their responsibility.

When the accusation spread in England that Roman Catholics could not be good citizens because they were “constrained” by the decisions of the Pope, the rumor became stronger when the Catholic Church dogmatically defined the infallible magisterium» of the Pope. However, this definition did not give the Pope more authority, nor did it suffocate the freedom of thought of Catholics[6]. Roman Catholic citizens were still personally responsible for their behavior before civil authority.

In his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, Newman emphasized that good citizens are necessary for society; these citizens should be loyal and committed to their faith. Consequently, Newman pointed out the areas of conscience that are governed by the authority of the church and the areas where Catholics are free to decide on their own. The basic principle of his explanation is that authority informs the conscience and makes it whole without replacing it or ignoring it. When a legitimate authority governs, obedience to its suggestions contributes to the freedom of those who obey that authority.

The objective separation of the two authorities — civil and religious — allows sufficient space for those who participate in both; in a civil society as in a religious society, persons may exercise their freedom completely. Internal harmony is the result of assuming that one’s self is the beginning and cause of his/her own acts, and so responsible for their effects.

- Four Deviations in the Relation between Temporal and External Matters

One can consider four vices in regard to temporal and eternal matters.

The first two transgress the principle of independence of the authorities who represent each of these areas.

The other two transgress the principle of interior harmony in the conscience of a person who is simultaneously a member of civil society and a religious believer.

In regard to the present study, these last two vices are of interest insofar as they were treated directly by Newman in his University Sermons and in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk.

Before treating these tendencies, it may be helpful to recall some historical events that exemplify the collision of the two powers.

In England, some monarchs tried to impose their will over conscience, over the Church, and even over the natural law. This collision of power resulted in the deaths of Thomas à Becket and Sir Thomas More. Likewise there have been occasions when church officials have tried to meddle indiscriminately in matters that come under the competency of the state.

Such was the case of the liberators of Mexico, Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos, both of whom were parish priests yet rose up in arms to start a war, which was strictly political.

The next section will explain the two vices that separate loyalty to the faith and to the Church from patriotism — loyalty to one’s country.

Newman spoke extensively of these last two vices that internally separate the temporal and the eternal; these will be mentioned in the final two points of this presentation.

For Newman, «a worldly mentality» is one which is more interested in things of this world than those that are eternal.

When worldly interests prevail, our conscience loses its focus.

A person who pays more attention to the exterior than the interior gradually becomes restless and disoriented.

Newman thoroughly explained «worldliness»: its causes, its different nuances, the sophisms that justify it and the procedures that help the conscience to overcome the reduction of one’s life to merely temporal goods. This is the central issue of his University Sermon VII, which was preached on Easter Sunday May 27, 1832, with the title: Contest between Faith and Sight”.

The three causes[7] of «worldliness» according to Newman are:

- The loss or deterioration of the conscience regarding religious and ethical principles which give us the capacity to use our freedom responsibly

- The obscuring of reality in relation to the effort and resignation that the virtuous way demands

- The contradiction between life and faith, thereby subverting the interests of society and people toward material goods. In their profession, they act as if they were atheists, but in their families they act as believers.

In the end, a «worldly outlook» is privileged because the idea that a revealed religion is a serious handicap to their aspirations becomes fixed in their mind. Since they do not want to abandon their plans, nor do they want to offend other people, they just let life go by[8] When a problem arises, they are doubtful and easily choose immediate gratification in preference to more substantial goods.

«Worldliness» has several degrees:

- First, those who relegate religion to a private sphere of their lives.

- Second, those who acquire the habit of distinguishing and separating their public and private obligations and passing judgments about them without harmonizing the two obligations.

- Third, those who theoretically accept a series of affirmations as doctrinal truths but in reality are not convinced enough to be firm and conscientious about the religion they profess.

- Fourth, those who maintain the fundamentals of the faith but lose its importance. They trim dogma in order to seek unity of feelings with others, not in order to achie doctrinal unity.

The most frequent sophisms used by worldliness to justify itself are:

- Evil should be accepted because it exists

- To consider an elevated morality is extravagant

- Not to believe that society can be improved and so to live for oneself

- Religion is an obstacle to free decisions

- Not to identify any restriction to one’s own plans

- Each person has the right to create new ideas that will satisfy himself/herself

- Something cannot be false if it is said all the time and everywhere

- The number of people who perform an act indicates the dignity of that act until it demands the acceptance of it as a law.

This last sophism seems like a prophecy. During the last couple of years, there have been a great number of cases in which if an evil act were committed by an isolated person, it would clearly be robbery or assassination. However, it is considered “good if this same act is supported by coalitions of different authorities or of the majority”. In other words, worldliness is the result of darkening reality.

As to solutions, Newman returned to a recurrent theme. The influence of imagination in regard to worldliness is an important element to consider because if we focus our imagination on higher goods, we have a concrete and efficient method at hand to overcome worldliness. We have won the battle when we learn to keep our own convictions even if we have to go against the stream. Accordingly, we will not blindly follow the majority. There is one more very efficient solution that is not always considered: do not trust yourself too much.

By knowing the causes of the inclination to the worldliness and having the firm determination to overcome them, it is possible to avoid the clouding the vision of reality, to understand the value of what is worthwhile goods and to use other goods only as a means.

3.2. Ultramontanism

The “ultramontane mentality” is the tendency to neglect temporal duties because they are considered to be irrelevant when compared to religious duties. This is another vice. In this case, the word “ultramontane” is being used generically because the “Ultramontanes” that Newman originally knew were a group of English Catholics (usually converts) who unnecessarily exaggerated the conciliar teaching on Infallibility and caused severe social problems in regard to the civil and religious relations of Catholics with people of other religions.

However, this term «ultramontane» is more appropriate for those who unnecessarily persist in a matter of faith in detriment to the temporal order. In an excessive form, it can become an injustice and imprudence. It is not the lack of good will but a matter of rigidity.

Ultramontanism is the vicious extreme totally opposed to worldliness. It is the situation when the conscience considers temporal matters to be of no importance thus focusing on the interests of ecclesiastical authority. Ultramontanism is an abuse committed by some people, not by the church as a whole. In reality, it cannot be completely achieved because no one can deny that there is a temporal condition to human life.

Ultramontanism is more common in people who serve as religious authorities. When they have some authority in religious matters, which may also include some consequences in temporal matters, confusion is caused among their followers because the limits between their civil obligations and religious responsibilities cannot be defined.

Perhaps this extreme position has its origins in the lack of understanding of what the Sovereignty of the Church and the Pope really means. Ecclesiastical sovereignty extends geographically around the world and faith has no frontiers nor is it affected by cultural differences. Accordingly, it can be falsely concluded that this sovereignty has no limits either in the external aspect nor in regard to internal human actions.

If Newman vigorously rejected worldliness from the time he was young, even to the extent of isolating himself from many customs of his colleagues, when he was older he challenged the narrow minds of those who intended to benefit the Church in detriment of its relations with other religions.

Conclusions

First:

The continuity of Newman’s thought in constant development is shown in his comments on the separation of civil and religious authorities.

Second:

From an historical perspective, the Irish situation made Newman reflect about these issues. In his youth, he understood the right of all citizens to participate in Parliament, no matter what religion they professed. Later, when he became a Catholic, he understood that the freedom of every citizen should be respected, whether this person was a soldier or an ecclesiastical authority.

Third:

Dogmatic and general moral teachings serve as a guide for everyone. In everyday life, each person must make his/her own decisions guided by theoretical norms in relation to a concrete problem.

Fourth:

When a person, besides being an authority, acts as a citizen, he/she should respect the rights and obligations of all citizens. He/she may express his/her opinions about civil or religious matters, but not as an authority. Every citizen must take responsibility for his/her own acts without involving third parties. If a bishop of a diocese votes for a certain political party, no one else has to know or even more, imitate him.

Fifth:

According to these principles, Newman rejected the confessional state for a country. In a confessional state, there would be discrimination against those who do not share the same faith as the government. Furthermore, aggression against the right to freedom of religion could be fostered.

Sixth:

Newman’s concern about moral issues led him to write about abuses of true freedom. A free person knows how to relate to reality. A worldly person attempts to reconstruct reality for personal advantage. An ultramontane tries to universalize her/his vision of reality.

Seventh:

Worldliness is associated with a lax conscience just as ultramontanism is associated with a scrupulous one. In the former case, religious goods are considered subordinate to temporal goods by the conscience while in the latter, the conscience is willing to sacrifice important temporal goods for the sake of a religious ideal that may not be all that relevant.

Eighth:

Worldliness seeks efficiency, immediate results and gratifications in accordance with pragmatism, superficiality and comfort. Ultramontanism forgets the importance of historical realities.

Ninth:

Both these deformations of the soul are overcome by a right conscience, which is personally responsible for the use of freedom in making decisions, both common and spiritual ones.

Tenth:

Truly free decisions conscientiously search for and achieve harmony between the temporal and the eternal. This is the teaching that Newman offered to his contemporaries in Oxford and in Birmingham. He fulfilled his ministry of preaching and teaching in a way that is still applicable.

[1] Cf. NEWMAN, J. H., Carta al Duque de Norfolk, Rialp, Madrid 1996, pp. 33-35.

[2] Cf. NEWMAN, J. H., Carta al Duque de Norfolk, Rialp, Madrid 1996, p. 108

[3] NEWMAN, J. H., Carta al Duque de Norfolk, Rialp, Madrid 1996, p. 111.

[4] Cf. ARISTÓTLE, Éth. Nic.

[5] Cf. NEWMAN, University Sermon VIII, n. 6 & ss.

[6] Cf. NEWMAN, J. H., Carta al Duque de Norfolk, Rialp, Madrid 1996, pp. 110-111.

[7] NEWMAN, J. H., University Sermon VII, n. 8.

[8] NEWMAN, J. H., University Sermon VII, n. 9.